How We Got Here

by Mike Smith

It was mid-September, 1695, hurricane season in Jamaica, when a 60-gun battleship, H.M.S. Winchester departed for England. As she rode the gulf stream current to the north, a severe storm blew her off course and on a very dark stormy night, she was impaled by coral off the up-per keys.

Seventy-five years later, the H.M.S. Carrysford, a 118-foot, 28-gun British frigate met a similar fate as she plied her way north through heavy seas. In 1824, Congress decided to do something about being able to warn sailors and they allocated $20,000 for a lightship to be securely moored in such a way as to warn ships off the reef. The ship, named Caesar, was a 220 ton two-masted schooner. Lanterns attached to each of the masts were designed to be seen from 12 miles. Unfortunately, the Caesar, as she was sailing from New York, encountered heavy seas and was grounded somewhere near Key Biscayne. The crew abandoned her, however, a salvage team re-floated her and made repairs. Finally, the Caesar, under the control of Captain John Whalton, was moored on its station.

The concept of a “lightship” did not work well, however, as ships continued to unexpectedly crash into the reefs. On December 19, 1827, while on duty during another storm, Captain Whal-ton heard the roar of cannon. He scanned the horizon and saw a large brig heading directly toward the reefs to the south of his position. As the ship got closer, he could clearly see her as bolts of lightning lit up the sky. She was heavily armed with 14 cannon and was being chased by a smaller, lightly armed ship. Both ships battled for some time when the larger ship tried to flee running into the reef with such a force as to tear a large hole in her hull and break her two masts. The smaller ship followed and hit the reefs also. The larger ship, Guerrero, sank. She was a slave ship with 700 Africans aboard, 41 of whom drowned. The smaller ship, was the H.M.S. Nimble and had been commissioned by British commissioners in Havana to patrol for slave traffickers. Unfortunately, the next morning several wreckers came out to assist and took the surviving Africans aboard only to be eventually sold again in Cuba.

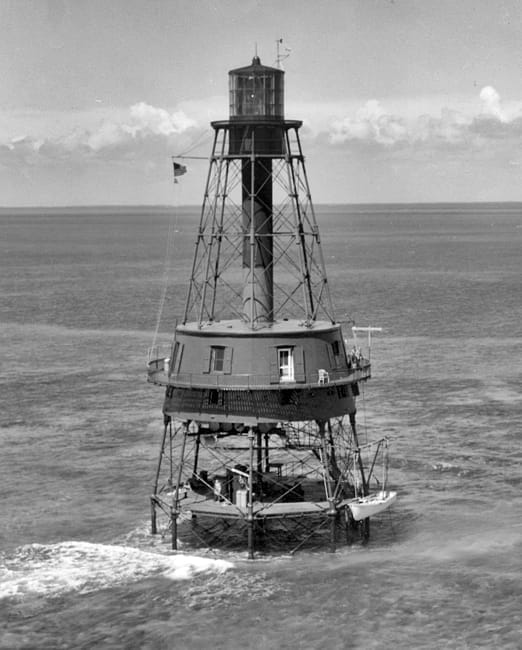

From 1833 to 1841, of the more than 300 shipwrecks recorded on the Florida Reef, 63 were caused by the same reefs that claimed the Winchester, Carrysford, Guerrero, and Nimble. Congress then appropriated funds to build a permanent lighthouse in 1848. The project was assigned to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers commanded by Major Thomas Linnard who died during the early stages of construction. The new commander was Lieutenant George Meade and the job was finished in 1852. In his report, he described the structure: “… composed of a framework of 9 piles, occupying the center and angular point of an octagon of 50 feet in diameter tapered up to 19 feet at the top. The floor is 33 feet above the water and the house of two stories is 20 feet high…”.

George Meade, 12 years later, would become Major General Meade who led the Union forces in the Civil War that defeated General R.E. Lee at Gettysburg.

Carysfort Light in 1962.

The light was called Carysfort Lighthouse (a likely bastardization of Carrysford), and became the oldest beacon of its kind in the United States. The light was manned by a crew 24 hours a day, seven days a week. On one occasion, a fisherman by the name of Brookfield, stopped by the lighthouse and delivered some magazines, newspapers and food to the keepers. The keepers asked Brookfield to stay overnight which he did. In the middle of the night, however, Brookfield heard an eerie groan that kept repeating. He went up to the tower and asked the keeper about the strange noise. The keeper replied, “Oh, that’s old Captain Johnson. You know he died right here in this lighthouse. He still comes around at night and groans.” Some think the groans are easily explained as being the expansion and contraction of metal with temperature changes. That might be true, but we all know temperatures don’t change that much day to day in South Florida, so maybe there are ghosts out there.

In 1962, the lighthouse was fully automated and the last livein occupants departed. In the late 1990’s a plan surfaced to convert the lighthouse to a marine research center, but the dream was never realized. Determined unsafe by the Coast Guard in 2014, the house was completely deactivated.

Carysfort Lighthouse remains a visual beacon for boaters marking the western edge of the Gulf Stream as it flows north around the Florida Straits. Fishermen, especially those fishing at night near the structure, still report hearing strange moans and groans. Maybe it is old Captain Johnson. Or maybe it’s just old father time gnawing away at the pilings.

View previous Articles form the How We got Here Series:

How We Got Here pt. 10

How We Got Here pt. 9

How We Got Here pt. 8

How We Got Here pt. 7

How We Got Here pt. 6

How We Got Here pt. 5

How We Got Here Pt. 4

How We Got Here Pt. 3

How We Got Here Pt. 2

How We Got Here